One vivid childhood memory for Emiliana Rodriguez was a game of soccer. That night, one of the players suddenly collapsed and was left lying motionless on the field. Not knowing what had happened, she, who was born in Bolivia, began to fear the night and the silent killer she called Chagas, a “monster” she was told only appears at night.

Chagas is a type of “silent and secretive disease” that is transmitted to humans by nocturnal insects. It infects up to 8 million people each year, 12,000 of them fatally, including a friend of the woman.

Emiliana Rodriguez, 42, moved from Bolivia to Barcelona 27 years ago, but has still not been able to get rid of her fear.

“The fear usually encompassed me at night. Sometimes I couldn’t sleep,” she says. “I was afraid of falling asleep and not waking up.”

Eight years ago, while pregnant with her first child, Rodriguez underwent tests that revealed she was a carrier of the Chagas virus. “I was in shock and remembered all the stories I had been told by relatives about people dying suddenly,” she recalls, also recalling her friend’s death. “I thought, ‘What’s going to happen to my baby?

However, Rodriguez underwent treatment to prevent the parasite from being transmitted to her future child through the vertical route. After the baby was born, she tested negative.

Meanwhile, in Mexico, Elvira Hernandez Cuevas had never heard of Chagas disease until her 18-year-old child was diagnosed with the silent killer.

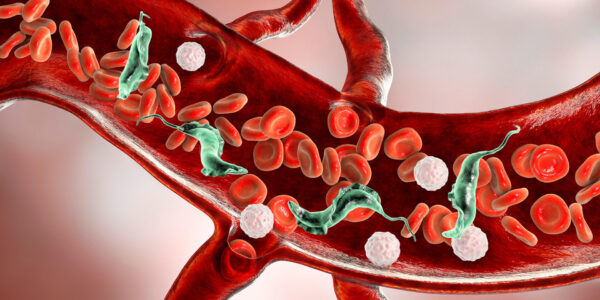

Idalia, 18, took a blood test in her hometown near Veracruz, Mexico, and her sample was tested, leading to a positive diagnosis of Chagas disease. The disease is caused by a blood-sucking parasite known as the kissing or vampire bug.

“I had never heard of Chagas disease before, so I started researching it online,” Hernandez told The Guardian. “I was horrified to see it referred to as the ‘silent killer’. I didn’t know what to do or where to turn.”

And Idalia isn’t the only one unaware of the disease.

Chagas disease is named after Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano Chagas, a Brazilian physician and researcher who first identified cases of the disease in humans in 1909. In recent decades, Chagas disease has spread to Latin America, North America, Europe, Japan and Australia.

Kissing bugs mainly live in the walls of old houses in rural or suburban areas and are active at night when people are asleep. Bed bugs transmit the T. cruzi infection when they bite a person or animal and then excrete feces on their victim’s skin. If the skin is accidentally damaged, such as a scratch, the feces can enter a person’s eyes or mouth.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Chagas disease affects about 8 million people in Mexico, Central and South America, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 6 and 7 million people worldwide are infected with the infection, most of whom are not even aware of their infection. If left untreated, Chagas disease can cause death. About 12,000 people die from the disease each year, and it claims “more lives in Latin America than any other parasitic disease, including malaria,” according to The Guardian.

Despite the discovery of these bedbugs in the U.S. (where about 300,000 people are infected), it is not endemic there.

Some people may be asymptomatic with Chagas disease, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 20-30% of them may develop heart complications decades later, which can be fatal, or gastrointestinal complications accompanied by severe discomfort.

The global case detection rate for Chagas disease is only 10%, making it a serious challenge to treat and prevent.

To get help, Hernandez and her daughter Idalia went to several doctors who had a limited understanding of Chagas disease and its treatments. “I was surprised, scared and distressed as I feared for my daughter’s life. In addition, I could not find reliable information, which added to my anxiety,” Hernandez shared.

It was only thanks to the support of a relative working in the health sector that Idalia received the treatment she needed.

“The Mexican authorities claim that there are not many cases of Chagas disease and that the situation is under control, but in reality this is not true,” Hernández states. “Medical personnel are not sufficiently trained, often confusing Chagas disease with other cardiovascular diseases. Many are not even aware that Chagas disease exists in Mexico.”

Chagas disease is listed as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization (WHO), indicating a lack of global health policy attention to the problem.

How to treat Chagas disease?

Colin Forsyth, head of research at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), explained that Chagas disease is considered neglected, particularly because it remains hidden in the body for a long time due to the lack of symptoms during the initial stages of infection.

Speaking about those who are susceptible to the disease and live in poor social strata, Forsyth continued: “The people affected simply don’t have access to influence health policy. There is a combination of biological and social factors that keep this disease hidden.”

However, as Chagas disease spreads to other continents it is becoming more visible and it is now known that it can be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ transplants and from mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth.

Professor David Moore, a consultant at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London, has set up the Chagas Center in the UK, whose focus is “to test and treat more patients and manage the risk of mother-to-child transmission in the UK.”

Moore stressed that progress against Chagas disease has been very slow, and according to the World Health Organization’s 2030 targets, he expressed doubt: “I doubt we will get anywhere near that target by 2030. It’s highly unlikely.”

Treatments for Chagas disease include two drugs – benznidazole and nifurtimox – that have been in use for more than 50 years, but as Moore noted, they are “toxic, cause unpleasant side effects and are not particularly effective.”

These drugs may be effective in treating children, but for adults, there is no guarantee that they can prevent disease progression.

As for serious side effects, Rodriguez recalls experiencing skin rashes, dizziness and nausea during treatment. She has successfully completed the treatment and has regular check-ups.

Moore added that developing more effective drugs for Chagas disease is essential to curbing its spread, but the process is not currently appealing to pharmaceutical companies due to financial aspects.

If you find a kissing bug, the CDC recommends not crushing it. Instead, gently place the bug in a container and fill it with alcohol or freeze it in water.

You should then take the container with the bug to a local health care facility or university lab for identification.

It is scary to think that these bed bugs could be lurking in the walls of our homes, like the horror stories we were told as children to teach us to fear monsters.

We hope that WHO will be able to fulfill its commitment to eradicate Chagas disease and other neglected tropical diseases.

Please share this story and help raise awareness of this under-appreciated problem!